Shared Landscapes

By Rebecca Wood Barrett

Humans have formed relationships between art and nature since the first images were sketched on cave walls millennia ago. Landscape and wildlife artists, through the meditative and immersive character of their artistic process, can teach us how to appreciate nature beyond the quick-Instasnap-and-move-on experience — that is, if we commit to paying attention to the endless unfurling moments of light, colour and shapes.

For artist Blu Smith of the Whistler Contemporary Gallery, his paintings are an exploration of “the light-filled spaces of the Canadian West Coast.” Smith would begin his workday by rising early and observing the spectacular sunrise and view of Mount Baker from his hillside home on the Saanich peninsula before descending into his basement to paint. “Once in the dark studio, I began to introduce that light into my abstracts and infused them with colour and a glowing sense of atmosphere that transformed them from two dimensions into the feeling of depth and space,” he says.

When he later moved to the lush, thick forest of North Saanich, the light of the sunrises was sadly gone. However, his painting “All Paths Lead Home,” with its rich, loamy shadows and glowing treetops, reveals how deeply he was affected by the scale of the towering Douglas firs and how light found its way through.

In contrast to the ephemeral and fleeting qualities of natural light, Floyd Elzinga’s massive sculpture, “Pine Cone,” imbues a local Whistler property with a raw and magnificent presence. “Using the medium of steel, Elzinga creates pine cones that appear as though they have just fallen from a tree,” says Tara Wolters, business manager of Whistler Contemporary Gallery.

Elzinga is drawn to duality and develops the idea as an underlying theme in his work. The pine cone as a seed is the origin of life — the small beginning of coniferous giants famed on the West Coast. And yet, there is a dichotomy in the seed’s purpose, which is to colonize. The artist notes that in some ways, the steel pine cones share more similarities with artillery and machinery — both providing the means to colonize — than the organic, sprouting pine cone seed.

whistlerart.com

Landscape artists are strongly influenced by where they live, and the colours, light, flora and physical geography will naturally affect the way they paint. In artist David Langevin’s case, it was the other way around — his painting influenced where he lived. Growing up in the Eastern Townships of Quebec, he discovered early in his career that his funky style of painting, and the subjects he was fascinated by — pine trees and rocks — were not to the taste of easterners. A friend suggested his work would catch on better out West, so he moved to Kamloops, B.C., the base from which he explores the province — hiking, backpacking and snowshoeing.

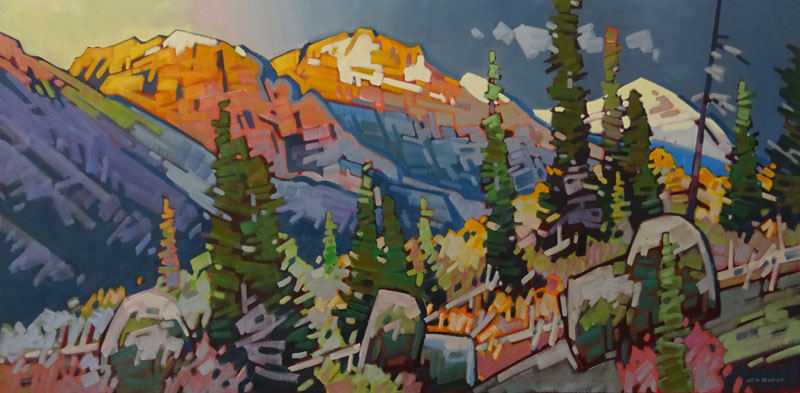

“When I’m painting and composing a painting, I really like diagonals and negative space,” Langevin says. “In B.C., there’s lots of both, because of the mountains.” His acrylic on cradled panel, “Why Is There Still Snow,” can be viewed at the Adele Campbell Gallery. It’s a perfect example of Langevin’s passion for diagonals and negative space — how bold, bright sunlight influences the beautiful tones and values in the colours of the sky, rocks, snow, and a lone, hardy alpine conifer.

Represented by the Adele Campbell Gallery, Cameron Bird is known for his vivid alpine landscapes and wild animals. From a young age, Bird spent years as a backcountry guide on horseback pack trips. By spending hours in the saddle in the wilderness of the Chilcotins, he discovered a deep appreciation for the angular aspects of mountain and scree slopes. Bird’s painting “Sundown Along The Duffey” truly captures the raw landscape of the mountain environment, while holding “the picture right on the edge of reality and abstraction,” Bird says, describing an approach he loves to explore.

To encapsulate the feeling of the countryside, and stay true to his style, Bird does not paint from photographs. Instead, he produces small sketches in black crayon, working in greyscale. This way, when he begins a full-size painting, he continues to render the scene in his style, and he gets to splash out and have fun with the colours.

adelecampbell.com

Artists Charlie Easton and Brent Lynch spend a great deal of time outdoors, observing the light and how it changes the landscape at different times of the day. And it is the long hours spent watching the daylight that makes their work feel authentic. “They really embrace getting in the backcountry and exploring various areas of the coast by kayak,” says Ben McLaughlin, communications director at Mountain Galleries, “and doing plein air studies under the natural light with the shifting cloud — with all the complexities that that entails — and using those studies to inform the larger canvasses.”

On a clear day, the drive up the Sea to Sky Highway to Whistler will reveal stunning views of the Tantalus Range and glaciers. It’s the sort of view you can spend a long time admiring, feeling struck by the immensity of the mountain spires. Easton’s painting “Tantalus Cloud Action” captures that same feeling, in the sweep of the icefields and clouds ascending, with the late afternoon sun adding remarkable and subtle nuances of colour to the white snow, glaciers and clouds.

Brent Lynch has a background in graphic design (he designed some of the original posters for Whistler Blackcomb in the ’80s), and his paintings often create an unusual shift in perspective by drawing the viewer’s eye to the unexpected. In “Diamond Sky Moraine,” the focal point is not the majestic peaks, but rather the transcendent night sky, alive with vibrant green, blue, yellow and orange sparks of celestial light.

There is a kind of magic when one falls in love with a piece of art, and often it is because the viewer has experienced the land and its wildlife in the same way as the artist: with reverence and awe.

mountaingalleries.com