RIOPELLE

The Call of Northern Landscapes and Indigenous Cultures

Exploring the Renowned Quebec Artist’s Life, Work and Influences

By Katherine Fawcett

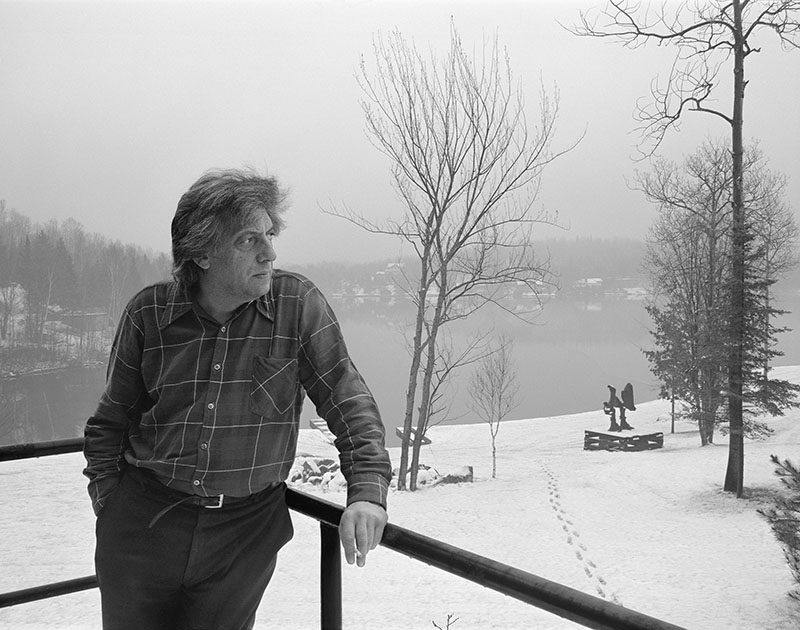

Basil Zarov (1905 (?)-1998), Jean Paul Riopelle outside of the Studio at Sainte-Marguerite-du-Lac-Masson with “La Défaite” in the Distance, about 1976,

black and white photograph. Library and Archives Canada, Ottawa. © Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021).

Photo © Library and Archives Canada. Reproduced with the permission of Library and Archives Canada/Basil Zarov fonds/e011205146

Afloor-to-ceiling black and white photograph of a man in a flannel shirt greets visitors to the Audain Art Museum’s ground-breaking exhibition Riopelle: The Call of Northern Landscapes and Indigenous Cultures. The man leans against the railing of a deck near a lake. He has a bushy head of hair, and seems oblivious to the cold. Behind him is a snow-covered lakeshore, trees and a garden sculpture. The man has a pensive look on his face, and a cigarette between two fingers.

Pictured is Jean Paul Riopelle, one of Canada’s foremost twentieth-century artists. The photograph was taken in the mid-’70s outside his Quebec studio when he wasn’t either in Paris or on an expedition to Nunavik or Nunavut. At this studio, Riopelle developed many Indigenous and northern Canadian motifs into complex and stunning paintings, prints and sculptures.

And this is where my exploration into the life and work of a Canadian legend begins.

The Riopelle exhibition originated at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Whistler’s Audain Art Museum is the first stop on a national tour. It features nearly 160 pieces and more than 150 artifacts and archival documents from collections around North America.

Dr. Curtis Collins, Director and Chief Curator of the AAM, is my guide. Once we step past the larger-than-life photo, we are surrounded not only by Riopelle’s own artistic works, but by an array of books, letters, photographs, documents, significant cultural objects and artwork by people who inspired and influenced him. Collins says it’s the most complex exhibition the AAM has ever hosted.

Born in Montreal in 1923, Riopelle studied at the École du Meuble de Montréal. He was a member of Les Automatistes, a politically and socially radical group of artists. In 1948, Riopelle signed Le Refus Global (Total Refusal), a manifesto rejecting the traditions of Quebec art and culture, and shortly after that, he relocated to France. During the 1950s and ’60s in Paris, he established himself as an artist of international consequence along the lines of Jackson Pollock. While overseas, Riopelle became associated with the Surrealists, such as André Breton and Georges Duthuit, who collected Indigenous North American art and masks.

“It’s interesting,” Collins says. “Riopelle’s first access to Northwest Coast art was in Paris, not in Canada.”

Claude Duthuit photograph of Paul Rebeyrolle, Riopelle, Jacques Lamy and Champlain Charest on a fishing trip, about 1975, print 2021, black and white photograph. Archives Yseult Riopelle.

© Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021). Photo Claude Duthuit – Archives Yseult Riopelle

Noah Arpatuq Echalook (born in 1946), Woman Playing a String Game, 1987, dark green stone, ivory, hide, 26 x 39 x 24 cm. National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa, purchased in 1991. © Fédération des coopératives du Nouveau-Québec.

Photo NGC

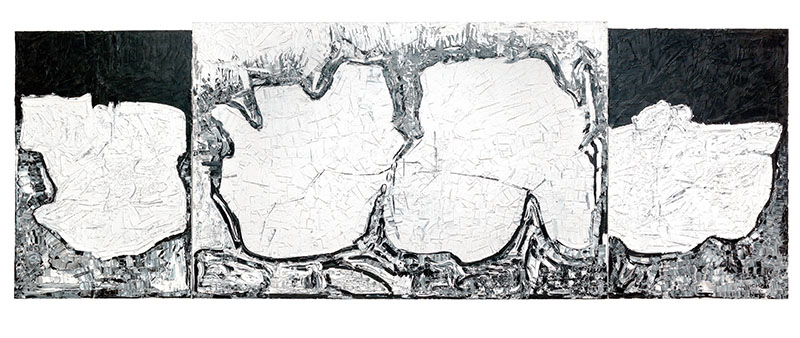

Jean Paul Riopelle (1923-2002), D’un long voyage (triptych), 1973, oil on canvas,

162.6 x 355.6 cm. Private collection. © Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021). Photo archives catalogue raisonné Jean Paul Riopelle.

As we meander through chronologically and thematically arranged rooms, I am amazed at the breadth of Riopelle’s work, and how the culture and landscape of northern Canada are interwoven. Indigenous art and artifacts that inspired Riopelle are placed alongside his own pieces. These include historical works from the First Nations communities of Alaska and B.C.’s Northwest Coast, and pieces by contemporary Indigenous artists such as Noah Arpatuq Echalook, Pudlo Pudlat, and Beau Dick. Pieces in the AAM’s permanent collection are referenced throughout the exhibit, and there is logic and continuity to the entire experience.

I am particularly taken by the centuries-old stone pile-driver artifact on display. It was used to build weirs and is the subject of a series of Riopelle’s delicate silverpoint drawings. Strings, from traditional Inuit string games, are featured in some of Riopelle’s enormous paintings. In other cases, the references are more abstract and cross-cultural, such as the Yup’ik-style masks crafted by the late Kwakwaka’wakw artist Beau Dick.

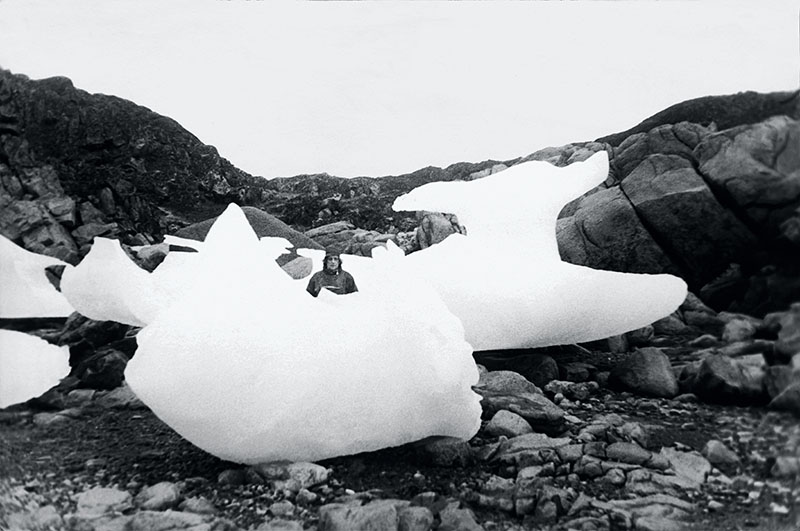

Perhaps my favourite part of the exhibit is what Collins called the “Iceberg Room.” The powerful black-and-white pieces in this section of the exhibit evoke feelings of a vast and stark environment. A large window in the room overlooks a Whistler snowscape, and a soundtrack of crashing ice enhances the immersive experience.

However, Collins is clear that the show is not without significant problematic issues; issues the AAM is serious about exploring and unpacking. Surrealists looked at Indigenous culture from around the world, Collins says, but they “never really dove into the fact that they had those items in their collections as a result of colonialism.”

The Indigenous art that Riopelle appreciated is mired in problematic circumstances around provenance. And because of that, when the show was first proposed several years ago, Collins was hesitant to say “yes.”

Claude Duthuit photograph of Riopelle in the Arctic, July 1977, black and white photograph. Archives Yseult Riopelle.

© Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021). Photo Archives Yseult Riopelle

Jean Paul Riopelle (1923-2002), Pangnirtung (triptych), 1977, oil on canvas,

200 x 560 cm. Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, achat grâce à une contribution spéciale de la Société des loteries du Québec. Inv. 1997.113.

© Estate of Jean Paul Riopelle / SOCAN (2021). Photo MNBAQ, Idra Labrie

However, after engaging several Indigenous academics and artists — including Xwalacktun, AAM board member and Squamish Nation artist — to see what their approach was to the material, Collins was able to come to terms with the idea. He says it’s the responsibility of the museum to acknowledge that the works in the exhibit have been removed from their ceremonial function, and they’re no longer in the hands of the makers or the ancestors of those makers.

“It doesn’t resolve any of these issues,” explains Collins, “but it kind of opens up a constructive space.”

Pieces in the AAM’s permanent collection are also contextualized in a way that invites conversation about appropriation. For example, a glass showcase featuring West Coast First Nations art is positioned so that the viewer sees Emily Carr’s paintings as background to representations of those who were on the land long before her.

We exit the special exhibition space into the bright hallway of the AAM. It’s a thrill to be in such an exquisite building, surrounded by trees and mountains. This exhibit has generated a great deal of attention in the art world and the media. Collins tells me that attendance numbers have broken records.

“It’s a unique show for here, but it’s in keeping with the style of show that the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts is known for, and the MMFA is one of the best museums in Canada. It’s nice to be in league with them, hosting this.”

Collins tells me how impressed the organizers and curators from Montreal were with how the exhibition came together and the show's overall look. When they attended the opening in October, “they were blown away.” But Collins is most proud when he talks about Riopelle’s daughter Yseult. She was also at the opening and loved everything about the AAM’s exhibition. “It was her first time here, and she was just over the moon,” he says.

audainartmuseum.com | 604-962-0413