Whistler Blackcomb 60 Years Young

Story by Caroline Egan | Images By Joern Rohde

Historical Images Courtesy Whistler Museum and Hugh Smythe

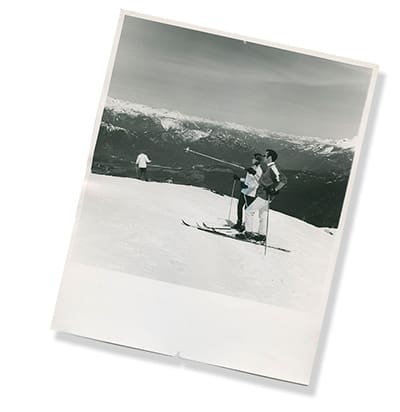

Photo Paul Morrison - Skier Mike Douglas

On Jan. 15, 1966, roughly 300 people gathered at the Creekside base of Whistler Mountain for opening day. The drive from Vancouver required navigating a single-lane gravel road, and lift tickets cost approximately $5. There were no grooming machines, just heavy, unskied snow that challenged even experienced skiers.

“[The] early days of Whistler [Mountain] were very difficult skiing, only enjoyed by true diehards, with long, skinny skis,” says Hugh Smythe, local legend and former president of Whistler Blackcomb (WB).

Smythe looks back on those days with warm feelings of nostalgia.

Those backwoods have been transformed into North America’s largest ski resort, setting global benchmarks for guest services, environmental stewardship, and mountain operations. WB’s 60-year journey reveals how competition, community, and an unwavering Olympic vision can build something extraordinary.

Many dreamers stoked the rise of Whistler, originally conceived as an Olympic venue. The mountain’s significant vertical drop made it ideal for world-class downhill ski racing. Whistler repeatedly bid for the Games while building a ski racing culture that would one day produce athletes capable of competing worldwide. In 2010, the Olympic dream finally came true. Along the way, major infrastructure upgrades changed the region forever.

The Whistler area’s competitive landscape has seen many dramatic shifts throughout its history. Fourteen-plus years after Whistler’s debut, Blackcomb Mountain saw its opening day — Dec. 4, 1980. It faced a daunting task.

“We had to out-service Whistler [Mountain] in every way possible to just even enter the game,” says Arthur De Jong, former Blackcomb Mountain president and current Resort Municipality of Whistler councillor. Then just 19, De Jong was there on opening day as a ski patroller. Speaking of that year as if he were frozen in time, he remembers that Blackcomb’s greatest asset was its ability to deliver exceptional guest experiences.

And so, “the service wars” emerged. Blackcomb began implementing a guest-first philosophy extending from the parking lot to the summit, even serving hot chocolate in the lift lines. Guests would come back to find their cars completely cleared of snow. One lift operator even gave an underprepared guest his pants for the day.

Despite such memorable moments, Blackcomb saw an unexpected closure for all of January 1981, while Whistler remained open. Blackcomb, along with various parts of the town, had seen its snowpack washed right out. It was a merciless strike from Mother Nature. “It rained and rained and rained, right to the top of the mountain, and washed all of the snow, like ALL of the snow, off the mountain,” Smythe recalls.

Those early struggles informed future planning, and the lessons resonated throughout each mountain’s operations: Anticipate guest needs, keep a close eye on the weather forecast, and plan accordingly.

Whenever Blackcomb evolved, Whistler responded. Each expansion pushed the other mountain higher and forced continuous transformations. By 1997, this competition forged the two identities into one — Whistler and Blackcomb merged.

The competitive drive that defined the rivalry became embedded in the resort's DNA. What started as duelling mountains became a unified culture of excellence, carried forward by staff who embody that same passion for pushing boundaries and delivering exceptional experiences. The infrastructure and terrain set WB apart, but the people who operate it transform potential into reality.

“You probably won’t find a more passionate group of individuals who just love these mountains, [and] love living in the Sea to Sky region,” notes Belinda Trembath, WB’s vice president and chief operating officer. Trembath arrived in town three years ago and quickly learned what kind of impact mountain operations can have on the resort. The mountain culture here thrives on diversity. Staff arrive from all over the world. Some stay for decades; others only months. Either way, the impression this place makes on a person can last a lifetime.

While Whistler as a destination resort is famed for its snow, it has so much more to offer. From winter pop-up mountain parties and fire and ice shows, to the world-renowned mountain bike festival, Crankworx, to the dining and arts scenes with events such as Cornucopia and the Whistler Film Festival, there’s plenty to experience here beyond the mountain peaks.

And these incredible surroundings allow all sorts of talent to flourish. Take Mike Douglas, the “Godfather of freeskiing.” This place transformed his life’s trajectory.

“I came from a small town [where] people told you why you can’t do things,” Douglas says. “Here, everyone was like, ‘Why not?’ This community lifted me on their shoulders.” For almost 38 years, Douglas has remained in Whistler, shifting from competitive moguls skier to co-designer of twin-tip skis, to filmmaker, to president of Protect Our Winters Canada.

“I've been trying to give back, whether through volunteer work or working with the Whistler Blackcomb Foundation or mentoring young athletes,” Douglas adds. His experience shows how WB became more than just a resort. It became an incubator for unconventional revolutions and athletic excellence.

“In the mid-’90s, skiing was dying,” Douglas says. “All the young people were getting into snowboarding. It was never our intention to save the sport; we were simply trying to save our own careers.”

And it worked. Twin-tip skis infused skiing with snowboarding's energy, creating a buzz that brought young people — some of whom could be found riding in summer programs where top athletes trained — back.

“The glacier scene was this who's who of the best of the best,” Douglas says. “It was so many good times and such a cool cross-section of learning and accelerating.”

The mountains have produced countless talented athletes, some of whom you still see competing today. Names like Rob Boyd, John Smart, Ashleigh McIvor, Maelle Ricker, Marielle and Broderick Thompson, Simon d'Artois, and Jack Crawford, just to name a few, all share a history here.

This journey extends to voices historically excluded from mountain sports. Sandy Ward, professional snowboarder and Líl’wat Nation member, had some barriers to overcome to get to where she is.

“I didn't have an instructor, so one of my buddies just brought me up to the top of Whistler [Mountain], and was like, ‘I don’t know, you just do this,’” explains Ward.

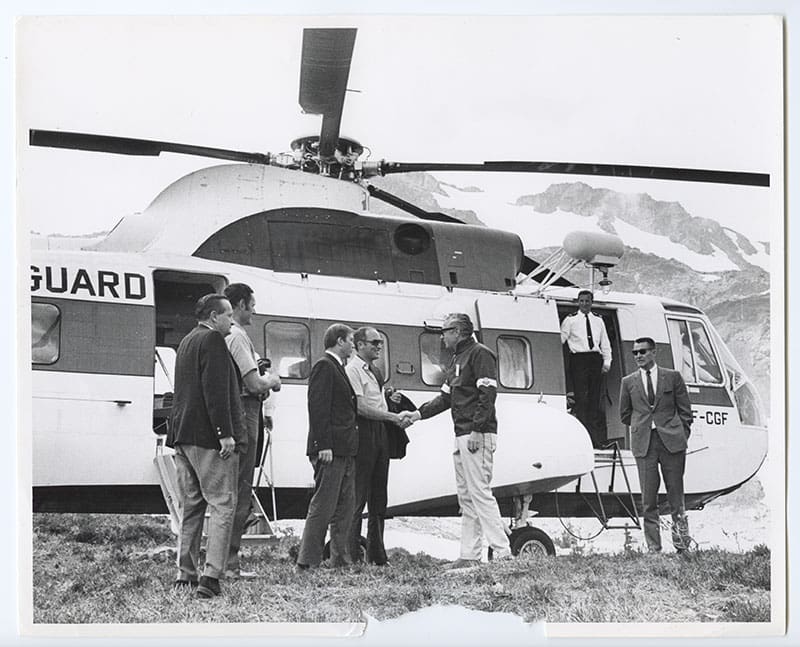

Center, Hugh Smythe

Second from right, Hugh Smythe

Ward still works as an instructor at WB, has co-founded Indigenous Women Outdoors, and also runs the Lil’wat Nation Qwíxwla7 Ski and Snowboard Program, which was launched in partnership with the Vail Resorts Epic Promise program.

“I got my instructor certification through the First Nations Snowboard Team. They gave us the certification so that we could teach the younger generation,” she says. “That was a really cool way of going full circle, and now I’m running the program.”

When asked about her relationship with WB and Vail Resorts, Ward acknowledges the mountains’ involvement. “I really appreciate all the support they’ve given Indigenous Women Outdoors and my youth program,” she says.

Belinda Trembath

WB prioritizes both its human and natural assets and has learned some lessons along the way. After an accidental fuel spill in 1993, De Jong turned to net-zero initiatives when most considered the idea unrealistic. In 2010, a micro-hydro plant opened on Fitzsimmons Creek and began generating electricity for the B.C. Hydro power grid, producing an amount equivalent to WB’s annual consumption. It immediately became an industry benchmark.

“We realized we had to become an inspiration,” De Jong says. “If we could inspire global tourism through resource efficiencies and lowering greenhouse gas emissions, what we’re doing [would] become really meaningful.”

Douglas sees the resort’s influence as its greatest environmental asset. “Us going to net zero in Whistler is not going to solve climate change,” he says. “But if we lean into the government and create this idea that you can do this stuff well, and spread that idea, we have a much better chance of multiplying our effect across the world.”

The environmental legacy continues to influence operations today, with sustainability practices spreading across the resort.

As WB enters its seventh decade, it’s focused on bringing its fundamentals into the future. While there’s still a way to go, recent work with the Rick Hansen Foundation to make its buildings more accessible and co-hosting Invictus Games Vancouver Whistler 2025 demonstrates its commitment to adaptive skiing and riding.

“Whistler Blackcomb hasn’t and doesn’t stand still,” says Trembath. “It has been constantly changing and evolving. That is what it is all about.”

This journey proves what can result when vision meets perseverance, and even after all these years, WB continues to lift dreamers onto its shoulders. whistlerblackcomb.com

To learn more about the history of Whistler Blackcomb and much more, visit the Whistler Museum, located at 4333 Main St. whistlermuseum.org