AUDAIN MUSEUM

A Journey Through 10 Years of the Audain Art Museum

Story by Katherine Fawcett

Geoffrey Farmer, The Good Sweeper, 2017 - 2025. Theatre backdrop (1939), foam, plastic, pigment, cut images, foam core.

Audain Art Museum Collection. Purchased with funds from the Audain Foundation. Courtesy of the Artist and Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver.

Installation View Photo: Joern Rohde

On March 12, 2016, a striking new building opened quietly in Whistler, changing the cultural landscape of British Columbia. Born from the vision of philanthropists Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa, the Audain Art Museum (AAM) set out to create a place where world-class art could coexist with the landscape, histories, and communities that inspired it.

Few predicted how profoundly the AAM would succeed. “I don’t think people expected how much of an impact this place would have,” says Dr. Curtis Collins, the museum’s director and chief curator. “Here we are, 10 years on,” he adds with a grin, “and we’re kinda busting.”

Today, the AAM is one of Canada’s most respected cultural institutions, renowned for its extraordinary Permanent Collection, adventurous exhibitions, and bold architectural presence. Many visitors come to Whistler for skiing, mountain biking, lakes, and fresh air; however, they leave talking about the museum — its serene cedar-clad hallways, its impressive, luminous galleries, and its sense of calm and curiosity in the heart of a high-energy resort town.

Much of that confidence rests on the strength — and the evolution — of the AAM’s Permanent Collection. What began with Audain and Karasawa’s foundational gift of 225 works has grown to more than 300, thanks to donations, acquisitions, and new commissions. The museum’s curatorial philosophy is based on openness: a willingness to revisit history, expand representation, question past blind spots, and present as much art as possible to the public. “We’re becoming known as the place that gets the works on display,” Collins says. “They’re not hidden forever.”

Curtis Collins, Director & Chief Curator in the Audain Art Museum vault.

Photo: Joern Rohde.

Installation View Photo: Joern Rohde

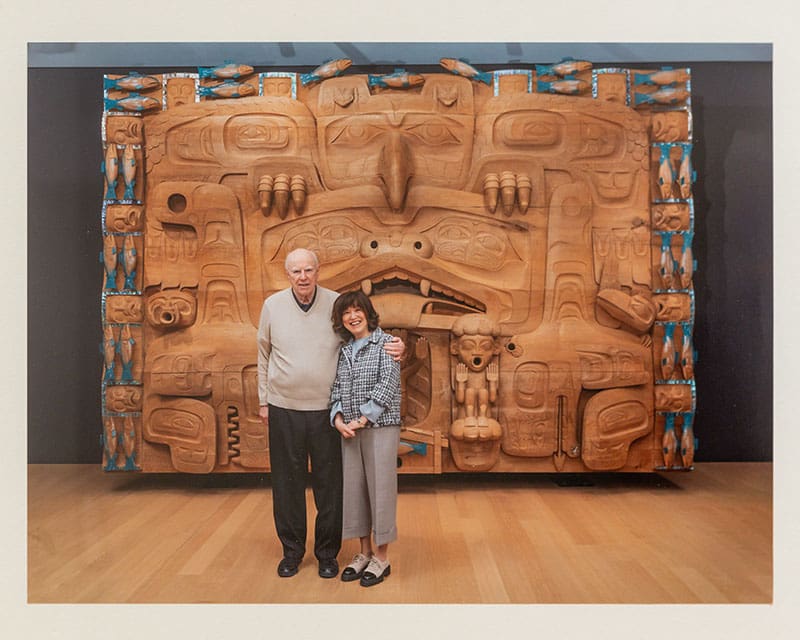

Michael Audain & Yoshika Karasawa standing in front of James Hart, The Dance Screen

(The Scream Too) (detail), 2010-2013.

Photo by Christos Dikeakos.

Geoffrey Farmer, The Good Sweeper (detail), 2017 – 2025.

Theatre backdrop (1939), foam, plastic, pigment, cut images, foam core.

Audain Art Museum Collection. Purchased with funds from the Audain Foundation.

Courtesy of the Artist and Catriona Jeffries, Vancouver.

Photo: Oisin Mchugh.

Kicking off with Geoffrey Farmer

The 10th anniversary celebrations are already underway with Geoffrey Farmer: Phantom Scripts, filling the Upper Galleries. Farmer — internationally acclaimed for immersive installations that explore memory, history, sexuality, and material transformation — brings a theatrical, probing sensibility to the museum.

The exhibition is part of the Permanent Collection, but this is the first time it has been displayed. Farmer calls the exhibition “a revision in time,” noting that artworks “change their minds in public as I learn to name where I stand and what I carry.”

Installation View Photo: Joern Rohde

Curtis Collins, Director & Chief Curator in front of Attila Richard Lukacs, Everybody Wants The Same Thing, (detail)1993. Promised Gift of Martha Sturdy to Audain Art Museum Collection.

Collins sees this fluidity as essential to the experience: “This exhibition offers a unique opportunity to encounter works from the Permanent Collection that continue to morph over time and space.” The result is a haunting, playful exhibition where sound, light, and everyday objects co-create meaning. It’s perfectly at home in the AAM’s architecture. “Out of all our spaces, this one is the most fascinating,” Collins says. “It really expresses the outside lines, inside.”

The Story Continues

As the museum enters its second decade, Collins is quick to emphasize that the AAM’s strength lies in its relationships with artists, collectors, donors, and communities across B.C., which includes deep, ongoing connections with Indigenous artists such as James Hart, Dale Marie Campbell, and Dempsey Bob. The museum also maintains open dialogue with Indigenous Nations regarding historic works such as ceremonial masks. “I’m not going to suggest for a second that it’s not problematic,” Collins says. “But we’re taking a very particular approach.”

This readiness to confront complexity rather than avoid it is woven throughout the galleries. Group of Seven paintings, for instance, face the historical truth that these artists drew heavily on Indigenous imagery during a period when Indigenous people were denied citizenship. “You have to have some sense of self-critique and historical context,” Collins says. “That’s part of the story.”

And the story continues to evolve. New acquisitions, new collaborations, and new interpretations constantly reshape the collection. “It’s fun,” Collins says. “We’ve got strong staff, strong trustees, a great membership base, and we’re part of the community. We’ve come a long way — and now we’re ready for what’s next.”

Installation View Photo: Joern Rohde

James Hart, Wasco, red cedar, pigment, copper and horse hair, 1998. This work by Hart is on display in the Crystal Gallery at the Audain Art Museum, Whistler until March 30, 2026 (private collection loan). The Wasco is a legendary Haida creature that lives in the ocean, with hybrid features of a killer whale and a wolf that include copper claws.

An Extension of the Permanent Collection

The current exhibition is absolutely electrifying. From Sea to Sky: The Art of British Columbia, drawn entirely from the Permanent Collection, features many works that have never been exhibited before. The museum’s three pillars — carving, painting, and photography — take centre stage, but it is in their interactions that the sparks happen: Indigenous carving alongside contemporary sculpture; photo-conceptualism next to political history; humour meeting horror.

“Every room is spectacular,” Collins says. Works by Robert Davidson, Lawrence Paul Yuxweluptun, Dempsey Bob, and others create deliberate conversations across time. Playful pieces such as Dogpile by Steven Shearer return to add contrast and levity. In just a few steps, visitors move from F.H. Varley to Fred Herzog to the award-winning golf-bag totem poles by Brian Jungen, and then to rare 18th-century European renderings of early West Coast encounters. The result is a collection that critiques, converses, and continually renews itself.

Growing, Morphing, Expanding

Growth at the AAM isn’t simply about adding more pieces; it’s about deepening its reflection of British Columbia’s cultural mosaic. “When we brought the original 225 works into the public realm, we had to ask, ‘Where are the gaps?’” Collins said. One gap was the representation of women artists. Increasing gender diversity has been intentional, but not superficial. “They’re here because they deserve to be here,” he notes. “It’s the work that leads.”

Recent acquisitions also highlight the many diverse communities that have shaped B.C., including those of Black, Asian, and mixed-heritage artists. A digital reproduction of Hogan’s Alley — a predominantly Black Vancouver neighbourhood displaced for freeway construction — connects local memory to global Black histories.

Collins recalls guiding a group of international G7 finance ministers through this section of the museum. “They were so impressed by how cultural difference[s] can be visualized,” he says. “That old phrase ‘cultural mosaic’ is actually pretty accurate.”

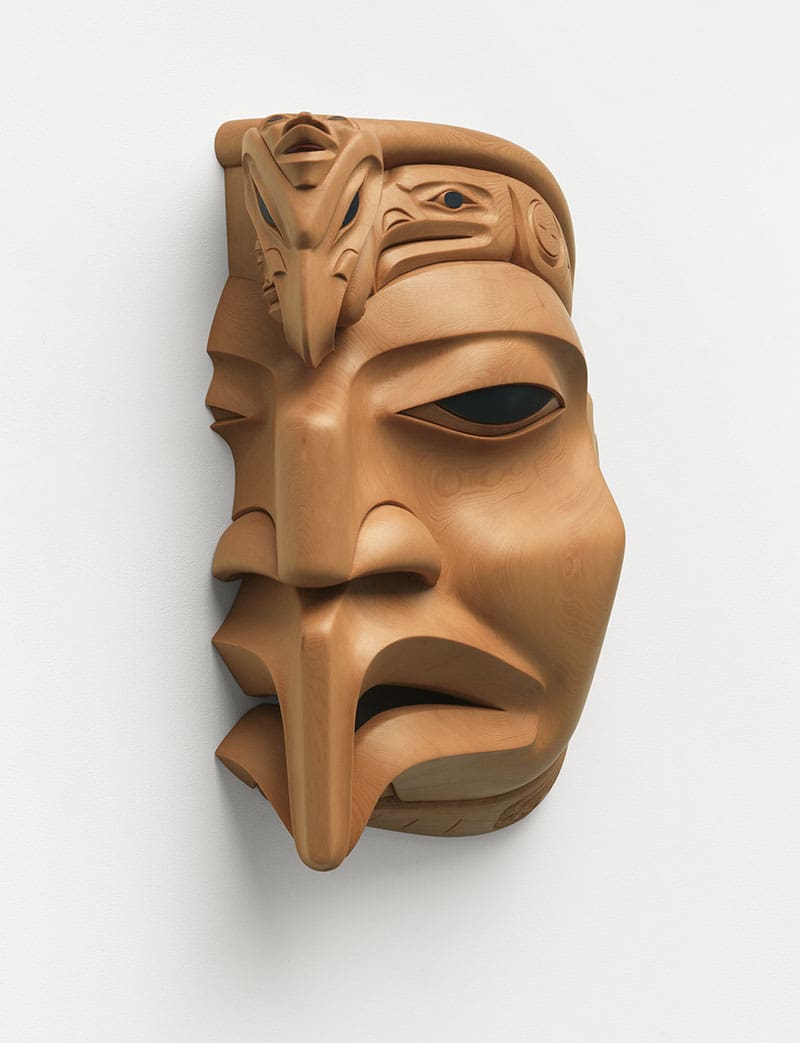

Dempsey Bob, Northern Eagles Transformation Mask, 2011.

Yellow cedar and acrylic pigment.

Audain Art Museum Collection. Gift of Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa.

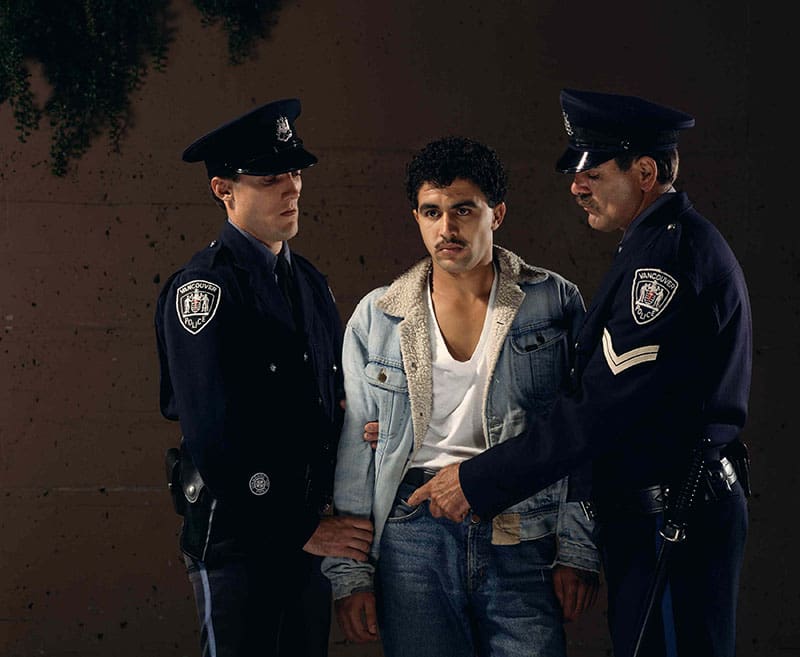

Jeff Wall, The Arrest, 1989. Transparency in lightbox.

Audain Art Museum Collection. Purchased with funds from the Audain Foundation.

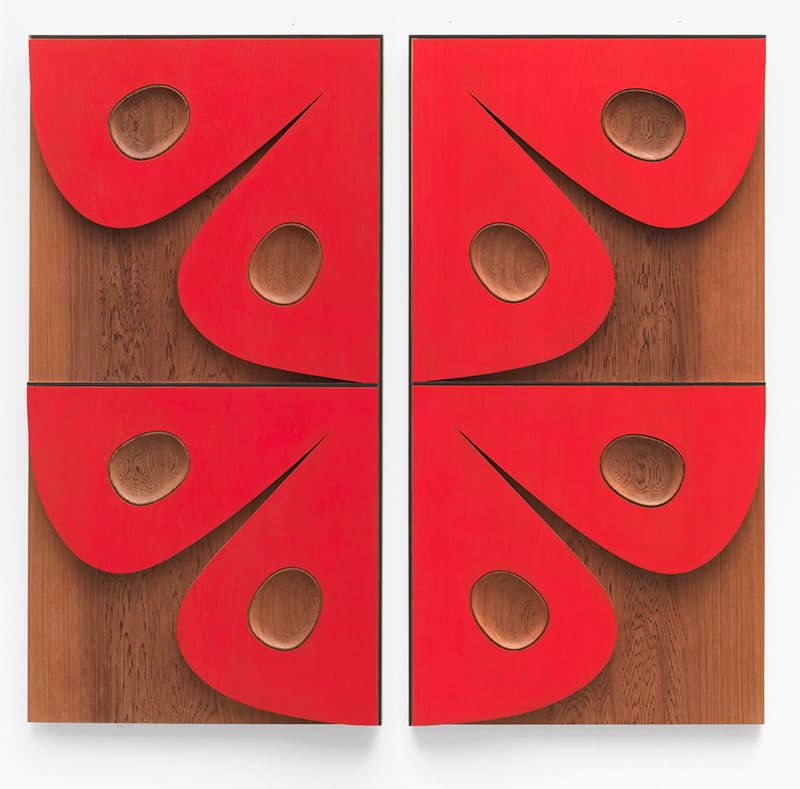

Robert Davidson, Relaxed Symmetry, 2003. Red cedar panel with pigment.

Audain Art Museum Collection. Gift of Michael Audain and Yoshiko Karasawa.

The Audain’s next decade is not expected to be about reinvention so much as deepening its purpose. Collins envisions a future of thoughtful, equitable acquisitions that honour both the museum’s origins and its evolving identity.

He’s also proud that the museum has earned an unofficial reputation as “Canada’s friendliest museum.” Formality is replaced by warmth and curiosity. Guests are welcome to come through in ski gear if they wish. Dinner nights, cocktail events, and lively, engaging programming ensure that the art remains accessible without being watered down. “People come here on holiday,” Collins says. “They want experiences that enrich without intimidating. We don’t pander, but we don’t lecture either.”

The upcoming exhibition calendar reflects that balance. A major Tak Tanabe exhibition arrives next summer, followed by a Stan Douglas show in 2027 — Douglas’s first in B.C. in more than a decade. In 2028, the museum plans to mount what Collins describes as a definitive contemporary and historic exhibition of Tlingit art, co-curated by Dempsey Bob and drawn from collections worldwide.

As the AAM celebrates its 10th anniversary, it stands as proof that world-class art can thrive anywhere passion and vision meet — even at the base of a ski hill. “You could drop this place in London or New York or Paris and we’d still have a profound effect!” Collins says with a smile.

Celebrate the Anniversary with a Night at the Museum

To launch its milestone celebrations, the museum will host an after-hours “Night at the Museum” on Jan. 31, 2026. The evening will begin with the founders and longtime supporters, then open to members and the broader community. “We’re hoping to attract new members, too,” Collins says. With a DJ, docent-led “Hot Spots,” and the entire building devoted to the collection, it promises to be a warm, spirited celebration of everything the Audain has built — and everything still to come.

audainartmuseum.com